By Evan Ackerman

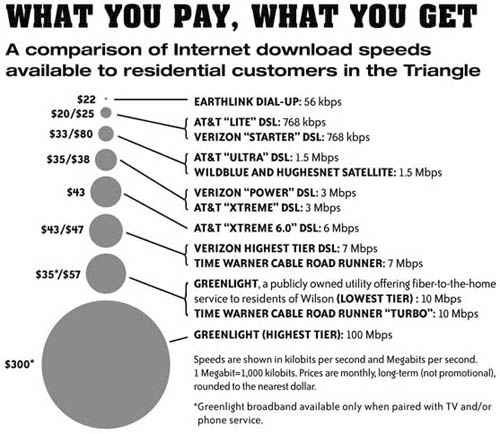

You may not realize it, but here in the US, our internet kinda sucks. We pay more money for less speed than just about everyone else in Europe and Asia. The town of Wilson, in North Carolina, got fed up with this and decided to form their own community ISP, called Greenlight, which was unsurprisingly able to compete so effectively with more traditional companies like Time Warner that you can’t even really call it competition:

For example, the city offers an expanded basic cable (81 channels), 10 Mbps (download and upload), and a digital phone plan with unlimited long distance to the U.S. and Canada, all for $99.95. A comparable plan from Time Warner Inc., with six fewer channels (no Cartoon Network, Disney, The Science Channel, ESPNU, ESPN News, or ESPN Classic) and lower upload speeds costs $137.95, for an introductory rate, which lasts a few months and then will likely be ratcheted up.

Greenlight also offers every single cable channel plus premium channels, unlimited phone service, and 20mbps internet for $170 (Time Warner’s fastest available service is 15mbps). And as if that wasn’t enough, Greenlight even has a 100 mbps service. Oh, and you know what else? They have 24/7 local phone support and actually respond to feedback from their community. See? It’s so much better, it’s not even funny. So, you’d think that in light of this, Time Warner would realize that their overpriced and underperforming services would need an overhaul to remain competitive in a world that depends so heavily on internet.

Instead, Time Warner is lobbying the North Carolina senate to pass legislation outlawing community ISPs. And it’s apparently working, too, which I can’t figure out because what could possibly be wrong with providing a better service to people at a cheaper price? Time Warner’s argument is that they can’t compete against a community-owned ISP that’s able to provide services at cost, but it seems to me that the real issue is that Time Warner’s services cost a lot, and they suck, and that’s why there’s no competition. If Time Warner wants to complain about competition, maybe they should first try to get competitive, instead of attempting to outlaw anyone who does things better than they do.

That's about the only good thing about Comcast broadband. They only have one level of residential service and over the past 4 years the speed has gone from 3mbps to 16mbps but the price does not go up with the speed changes.

Just another reason to dump Time Warner. They have about as much chance to stop city owned ISPs as does Microsoft to stop Linux.

mcman, not sure what podunk you live in but the Comcast here has 4 levels of residential service 15/20/30/50 mbps download (with powerboost) at costs ranging from $43 to $140 per month.

Don't get me wrong, Cable companies are the devil. I totally agree that a community should be able to setup and manage there own ISP, cable services etc. , but in Time-Warners defense, they have something called build-out requirements. They have to run lines and offer service to any area with certain specified population densities, even if it is not profitable.

One would think their attempts would fall under some anti-trust/anti-monopoly legislature or something

Not to be one of those nitpicky jerks who find every mistake there is, but do you mean Mbps not mbps? wouldn't mbps be millibits per second?

Comcast last year paid the state of Florida $150,000 to deal with this exact issue and the ambiguity that surrounded it. Each month, Comcast would contact the top 1,000 users of its 14.4 million user network network, regardless of how much data they had transferred, and warn them that they were violating the acceptable use policy. When users asked what the limit was, they were simply told that they needed to stay out of the top 1,000 user list—something impossible to know.

The state attorney general said that “a 'top 1,000' criteria, as previously applied, did not clearly and conspicuously disclose to the consumer the specific amount of bandwidth deemed to be excessive under Comcast's subscriber agreements.” In response, Comcast adopted the explicit 250GB/month cap.

Comcast last year paid the state of Florida $150,000 to deal with this exact issue and the ambiguity that surrounded it. Each month, Comcast would contact the top 1,000 users of its 14.4 million user network network, regardless of how much data they had transferred, and warn them that they were violating the acceptable use policy. When users asked what the limit was, they were simply told that they needed to stay out of the top 1,000 user list—something impossible to know.

The state attorney general said that “a 'top 1,000' criteria, as previously applied, did not clearly and conspicuously disclose to the consumer the specific amount of bandwidth deemed to be excessive under Comcast's subscriber agreements.” In response, Comcast adopted the explicit 250GB/month cap.